The Wise Casserole: Old Recipes as lessons in survival

I love old cookbooks.

So much.

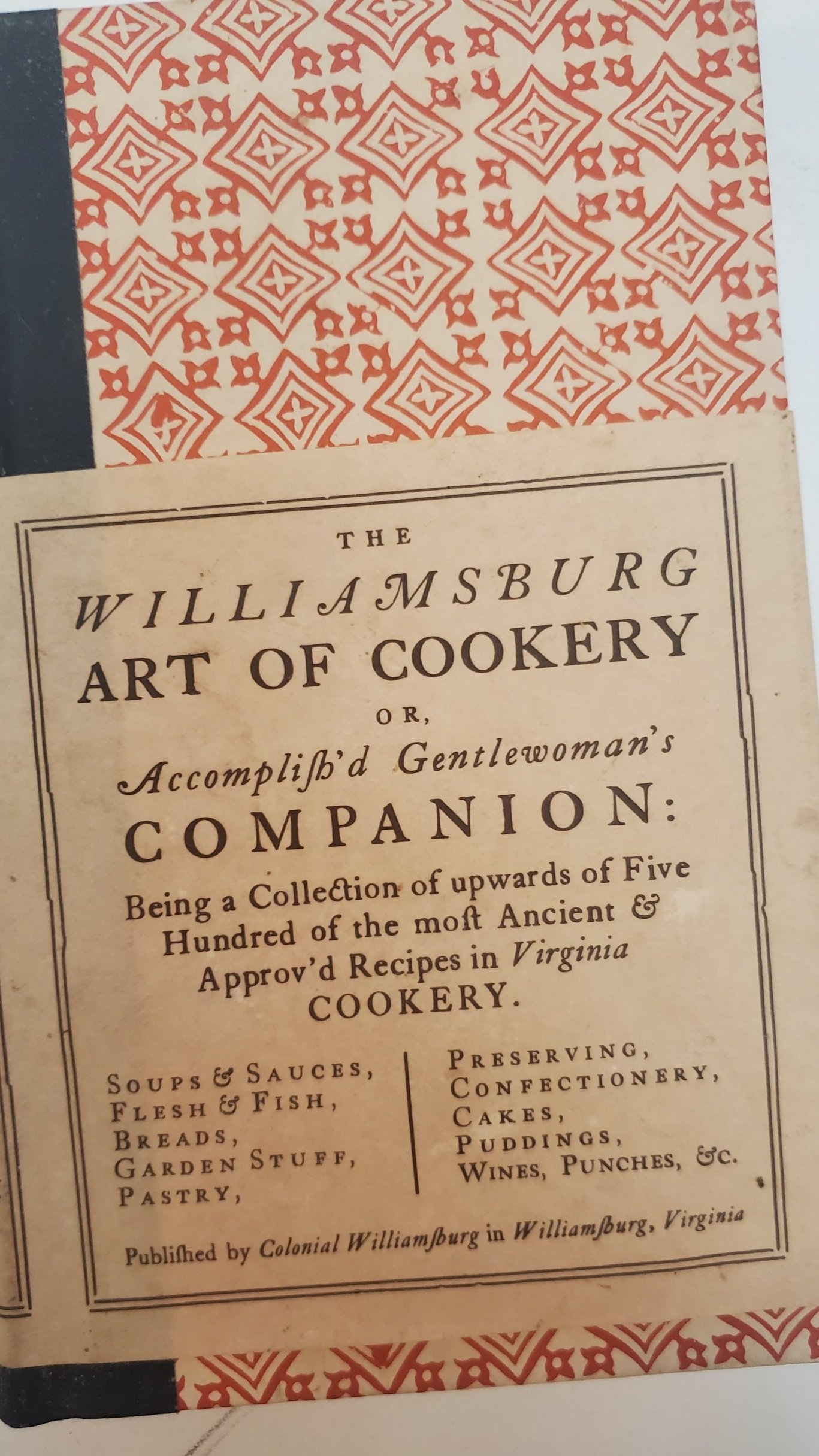

I am for sure among the people who love spending an afternoon slowly making my way through an antique store, and one of my favorite things to find is a obviously well-loved cookbook (or, better yet, personally curated recipe collection) from centuries past.

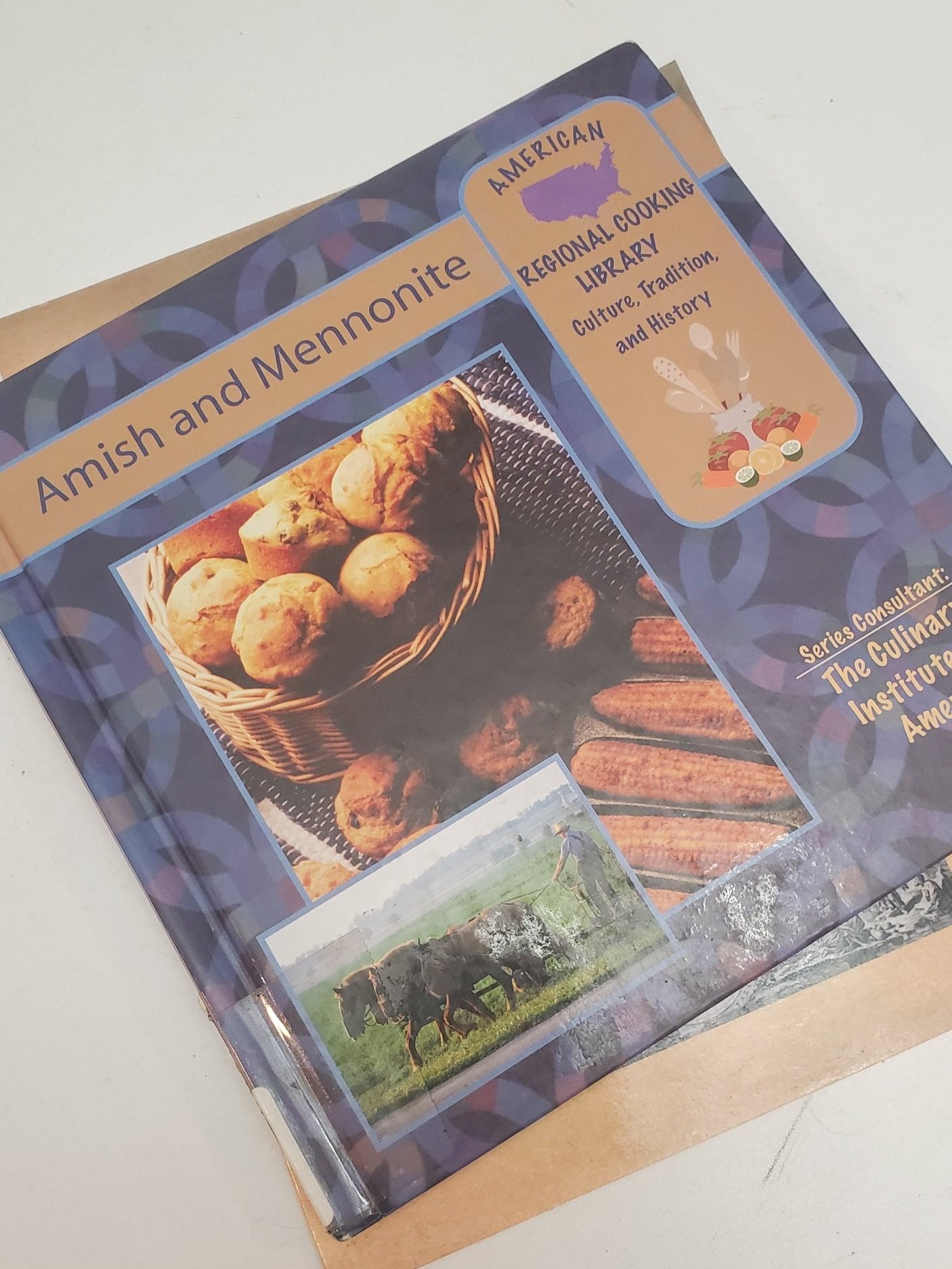

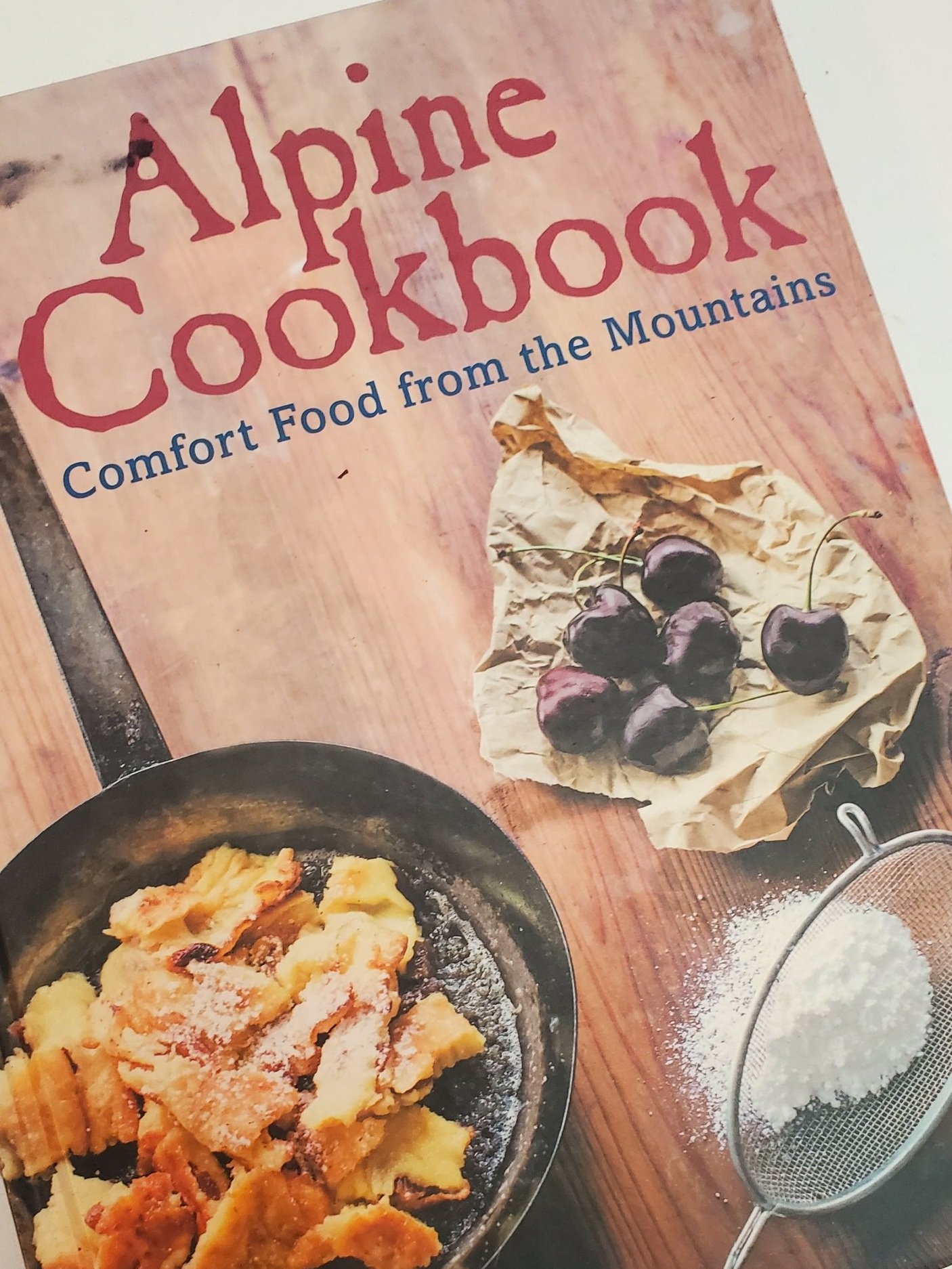

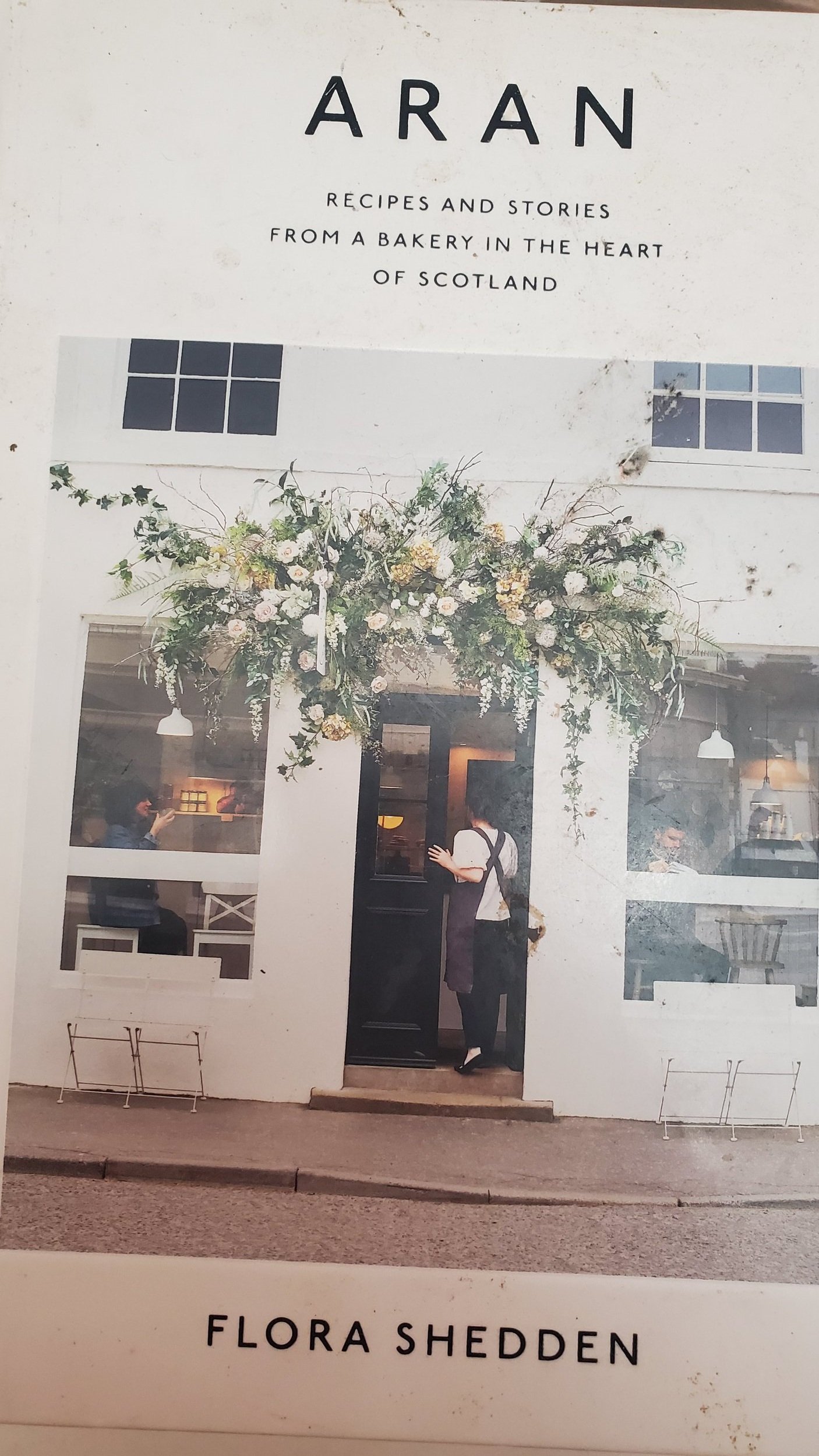

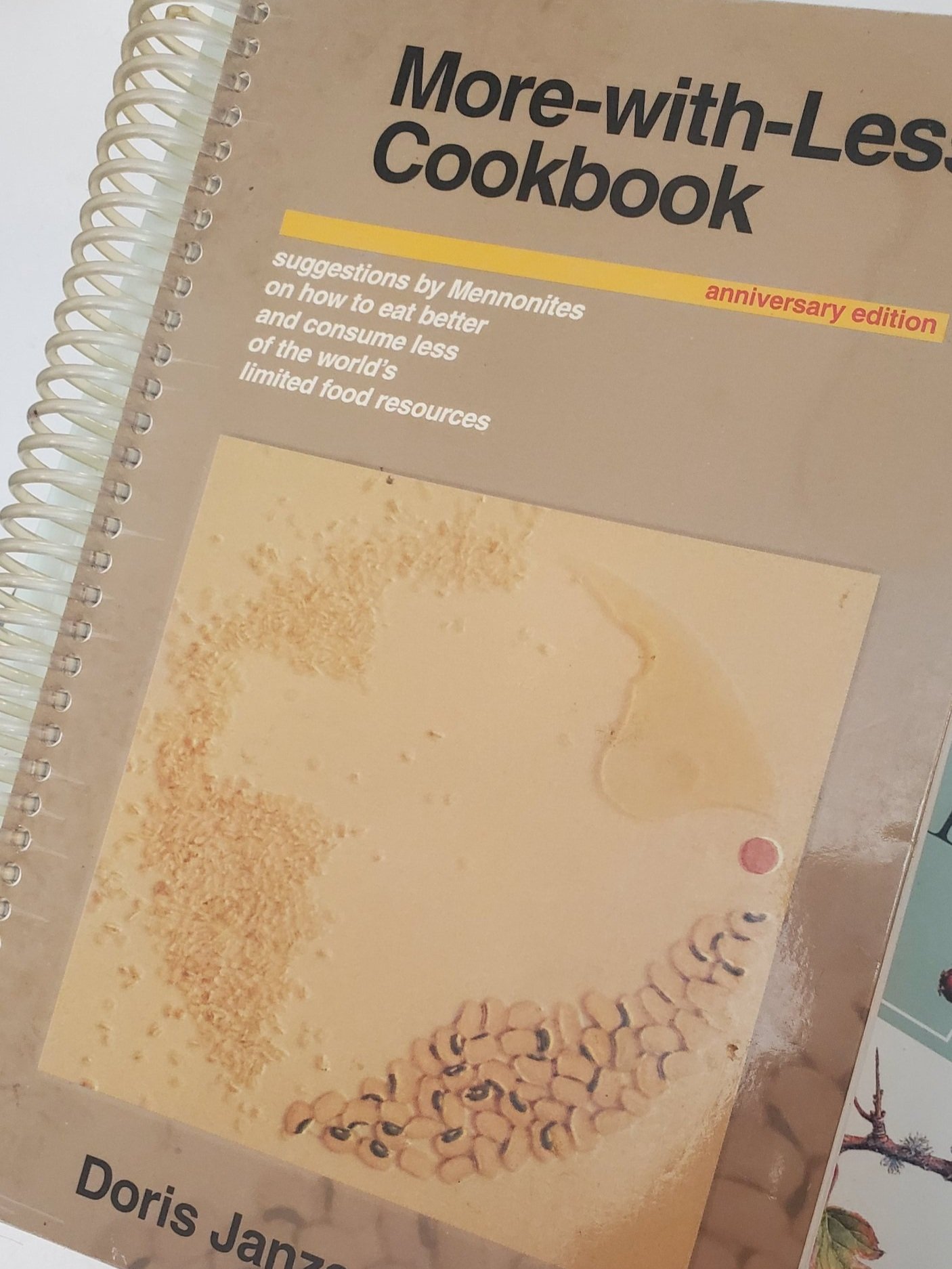

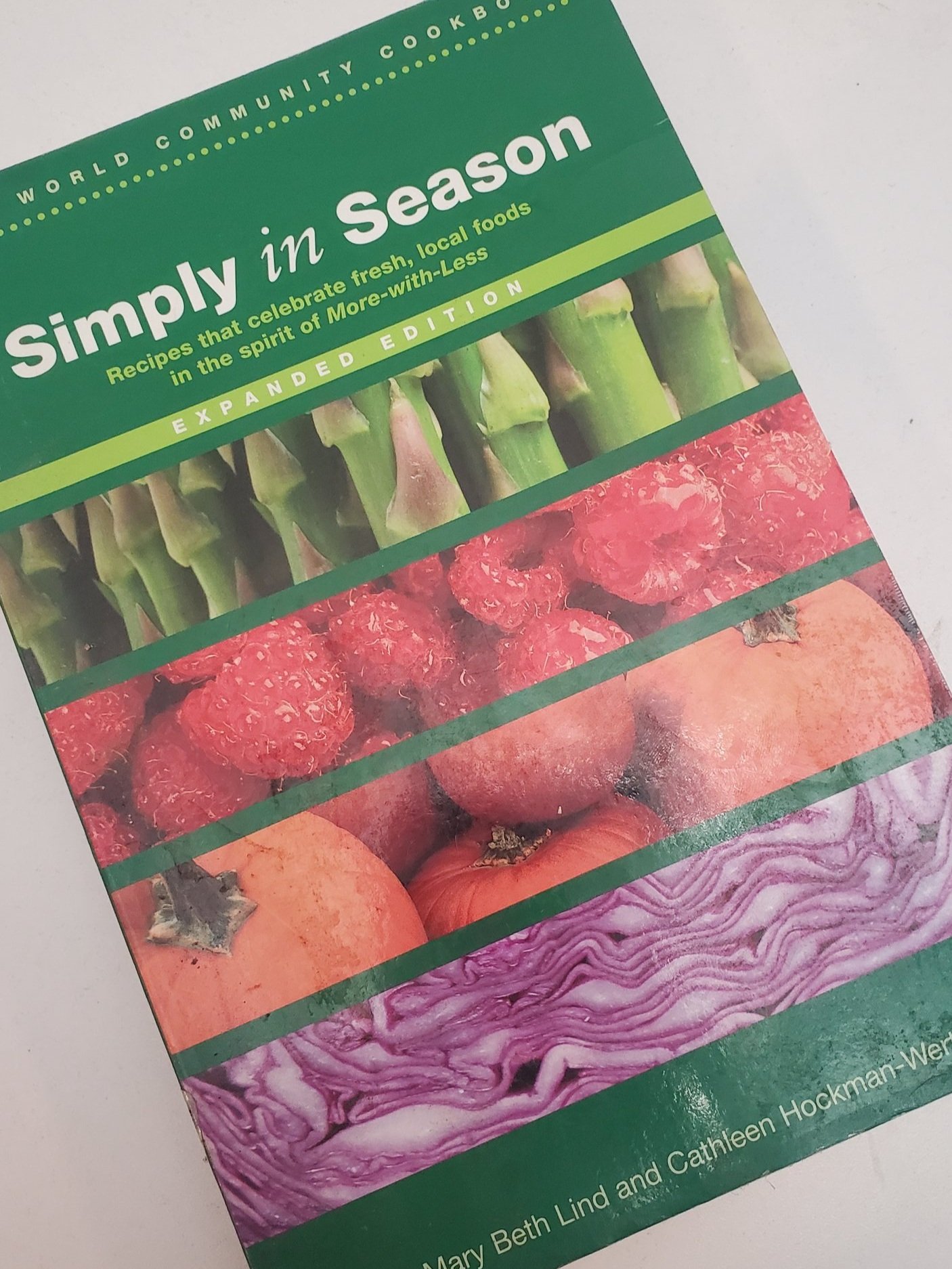

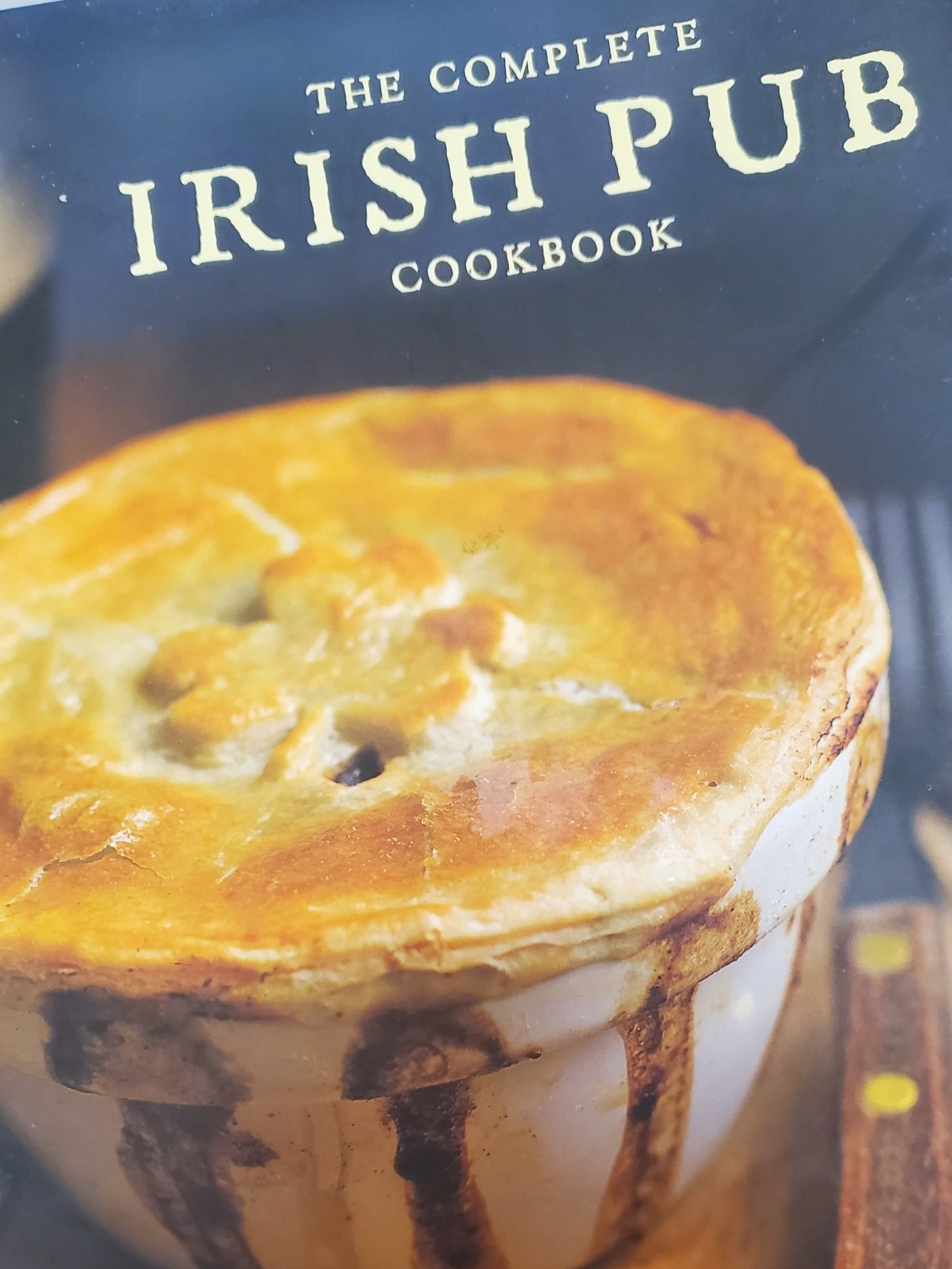

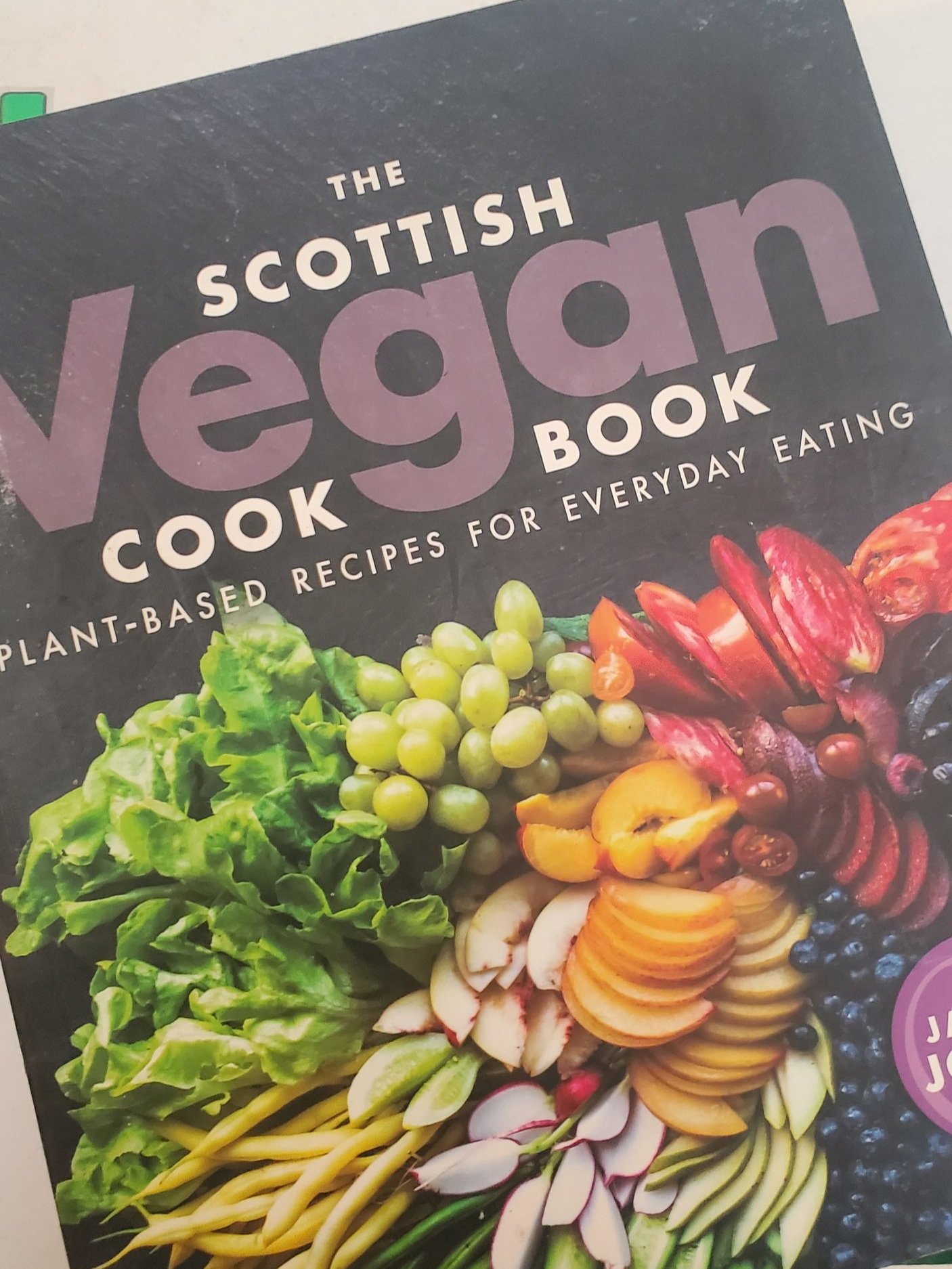

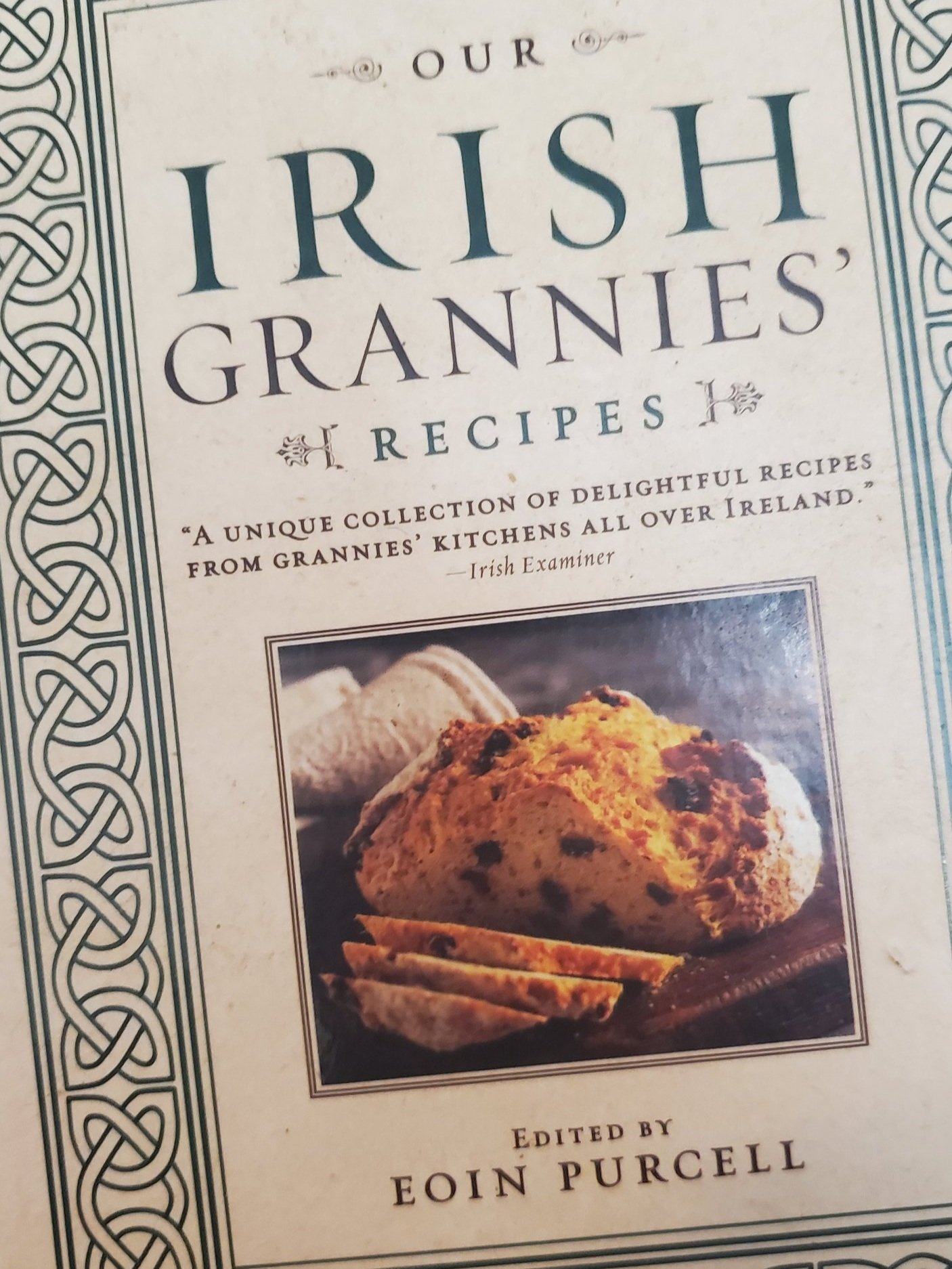

In addition to antique store finds, I also enjoy seeking out, learning from, and referring to cookbooks (and books regarding edible and medicinal uses of herbs and spices) that are focused on ingredients and recipes my ancestors would have used; this has resulted in a small collection of books related to traditional foods from Scotland, Ireland, Switzerland, and Mennonite and Church of the Brethren communities in multiple countries.

(Two of such special noteworthiness that they deserve their own gallery highlight are Edna Staebler’s classic recipe collections of “Mennonite Country Cooking,” Food that Really Schmecks and its unparalleled sequel, Schmecks Appeal.)

Just yesterday, I was tasked with deciding what potato dish to make, and knowing very well that my ancestors knew a thing or two about potatoes, I consulted some of these ancestral resources.

It was in doing so that I came across the recipe for Potato Deutscher (Dutch Potatoes, referring to the Dutch and Pennsylvania Dutch linguistic Anabaptist communities, not to Deutschland/Germany) that appears in the Mennonite Community Cookbook collection; this specific recipe is from the kitchen of one Mrs. Noah Ebersole of Birch Tree, Missouri.

The notes that I have added in this image are not an indication of the ways this recipe is lacking; rather, they are an indication of the strength and wisdom of these old recipes.

(They are also an indication that the legibility of my handwriting is not at its peak when I am scribbling down notes while cooking.)

(I will address the absence of seasoning and herbs/spices in the recipe later in this post: trust me, I am not so oblivious to the norms of whiteness that I don’t notice the failure to mention nary a one besides a mere teaspoon of salt and a paltry 1/8 of a teaspoon of pepper!)

While I made this dish, I was struck by the deep seasonal wisdom of this recipe.

This is a recipe for winter (especially the later stages of winter).

It is a recipe for survival.

It is a recipe for finding pleasure and richness in dark, tenuous, poor times.

Many folks who live in northern/temperate ecosystems know that potatoes are an important storage crop: when stored carefully, they can last until the early spring forageable foods and short, early-season crops start to make an appearance.

But still, sometimes the main concern isn’t the duration of the storage, but of having enough put away in the first place: stretching out what is there is of the utmost importance if the previous year’s harvest would be enough to last until spring.

That’s where the bread, eggs, milk, and sour cream come in.

One thing that a home with an active sourdough starter often has is a bit of bread that’s going stale.

Many of the grains that store best are also grains that tend to yield a dense, hearty loaf: whole wheat, barley, cornmeal, nut meal, and the seeds of forageable wild plants such as amaranth, dock seeds, and foxtail millet. When these loaves start to dry out a bit, they need to get used asap (lest they become chicken feed or end up in the compost pile); once they’re stale, they become a bit too much for human dentition to tackle.

And the vast majority (if not entirety) of my Anabaptist ancestors would have had chickens, and an only slightly smaller percentage would have also had a milk-giving animal of some sort, whether cow, goat, or sheep.

Right now, our fairly small flock of eleven hens and a roo is still bringing forth 5-9 eggs every day, even in the darkest days of the year and without any additional lighting in their coop.

We don’t have any animal friends on the farm who produce milk, but I do know that families with their own cow(s), sheep, and/or goat(s) who are at a stage of their life when they are producing milk can provide enough that a family needs to find ways (usually through various fermentation methods) of using and preserving all that is available to them.

The addition of bread in this recipe provides additional bulk to the casserole, as well as additional nutrient- and energy-density. Soaking it in the milk not only allows bread that otherwise might have had to be tossed on the compost heap to instead feed one’s family and community, but also gives the whole dish a protein boost with a readily available product to the Mennonite, Amish, and Church of the Brethren families who would have made this dish.

The “sour cream” in this recipe is not the product in a plastic tub that is available for purchase at your local grocer. Rather, this recipe refers to literal cream that has begun the fermentation process and has begun to turn a bit sour (note the use of the word “pour” rather than “spread”). As I note on the recipe, other cultured and/or fermented and/or clabbered dairy products will do: if you need something completely lactose free or vegan, you can add a bit of vinegar or lemon juice to the lactose-free or non-dairy “milk” of your choosing.

I actually made this connection because I recently read the section about sour milk in Julia Skinner’s amazing book Our Fermented Lives: How Fermented Foods Have Shaped Cultures and Communities. This section includes the following paragraph:

Dairy was very important to the ancient Celts, who hailed from many places in western Europe and whose diets varied between those places. This was especially true for the Celts within what is modern-day Ireland. The lush landscape meant lots of food for cattle, and dairy (and dairy fermentation) has been a staple on the island since pre-Christian times. And the Celts didn’t just like drinking plain milk—sour milk was key. Food writer Sam Dean writes that in 1690, “one British visitor to Ireland noted that the natives ate and drank milk ‘above twenty several sorts of ways and what is strangest for the most part love it best when sourest.’ Of particular note, the Celtic Irish drank what they called bainne clabair, milk that had been allowed to sit out just long enough to sour but not long enough to curdle. It is somewhat similar to yogurt. When Scots-Irish people immigrated to the southern Appalachian Mountains, they brought that tradition with them, calling it clabbered milk, or simply clabber.

The idea of clabbered milk may not appeal to as many folks nowadays, but there is wisdom in it: the processes involved in culturing and/or fermenting dairy products not only help to preserve dairy products, but they also reduce the lactose content of the dairy thoroughly enough that many lactose intolerant individuals can consume them without ill effects (Fermented foods and probiotics: An approach to lactose intolerance | Journal of Dairy Research | Cambridge Core and https://www.journalofdairyscience.org/article/S0022-0302(82)82198-X/pdf).

Ultimately, this recipe transforms a modest amount of one of the few fresh vegetables likely to be available consistently throughout the winter months into a hearty, warming, rich (and large!) casserole by adding products that are, likewise, among the few likely to be available throughout the winter and that are near the end of their use-by dates.

The result is a sizeable casserole that has all of the macronutrients (protein, fat, and carbs) that are necessary for human survival while relying primarily on using ingredients that could otherwise go to waste.

Okay, and now we need to address it: the absence of herbs, spices, and even basic seasoning.

This austerity winter recipe does not assume that a household will have any specific dried herbs or spices remaining in their pantries or apothecaries in late winter.

What it does assume, based upon the cultural norms of the community from which these recipes arose, is that the cook will have at least a rudimentary knowledge of what herbs and spices pair well with potatoes. Recipes from these times were bare-bones bits of information that contained within them massive amounts of subtext and assumption.

As such, I find it reasonable to surmise that any of the people Mrs. Ebersole expected to be reading her recipe would know that you could toss in a bit of any dried dill, or thyme, or nettle leaf, or oregano, or… that you were fortunate enough to have on-hand from the previous growing season. However, it would be unreasonable (and possibly borderline rude) for her to have presumed which of those herbs a reader may have on-hand at the time of year for which this dish was created.

With that said, I need to acknowledge that another common reason that the recipes from the cookbooks and family collections of many white Americans are so devoid of seasoning, herbs, and spices is directly connected to the legacy of chattel slavery and the ways that the labor of Black women was the very foundation of many white households. Many of the skills involved in growing, preserving, cooking, and elevating food are, quite simply, ones that a lot of white femmes (particularly those of a certain level of social and/or financial privilege) never needed to/got to learn.

Following the passage of the 13th Amendment, the ways that white women’s domestic functioning depended upon the labor of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people continued, whether directly (as in the case of having hired household staff) or indirectly (through reliance on factory-produced convenience products that were made by companies that profited from underpaid Black and Brown migrant farm workers and/or factory workers).

My sole reason for asserting the other explanation for the absence of herbs, spices, and seasoning in this recipe is precisely because it was written for members of Mennonite communities. I am not one to hold Anabaptist communities such as the Amish, Mennonite, and Church of the Brethren on a pedestal of supposedly idyllic communities of neverending peace and simplicity; there is no shortage of information regarding the harms that have taken place to vulnerable people and animals within these communities, and it is undeniable that their “communities” in the United States were built on stolen land.

But one area where the three Anabaptist churches did happen to be on the right side of history of is in regard to slavery: they were firmly and assuredly on the side of unapologetic abolition. That, combined with the insular nature of these communities, lends support to my hypothesis about the absence of seasonings.

My goodness: this is the most I have ever written about a single recipe before! Why, you may be asking, did I bother?

I think there is a deep wisdom to be found in this recipe.

I further think that it is a sort of wisdom that many people may need to be reminded of right now.

This is a recipe that, as I wrote earlier, is a recipe for survival and for finding pleasure and richness in dark, tenuous, poor times.

Times, perhaps, like these.

Maybe you live in a place where you have ample access to potatoes; maybe you don’t.

Wherever you live, you live in a place where there is a deep and rich context of people who have, through generations past, found ways to survive while caring for their families and communities.

Those times were not the same as now. This moment in history has no shortage of additional factors, including but not limited to the worsening severity of ecological destruction and the wars in Palestine, Russia and Ukraine, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Somalia, Libya, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Myanmar, Colombia,…

And also, there is some light to be found in the gifts of recipes like this, recipes that are (by virtue of their simplicity) a prayer for continuing life, an expression of faith that warmth and light will, indeed, find their way to us again.

![20240120_170002[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/615dd7cb7407ea38c4519be4/1705789102383-OLDZPD1O3EZ5QMFISYZA/20240120_170002%5B1%5D.jpg)

![20240120_170033[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/615dd7cb7407ea38c4519be4/1705789118375-382LOJ9R0I8HAMTFSQ1V/20240120_170033%5B1%5D.jpg)